Key quotes from the Rev. Jesse Jackson that define his political views

Written By The Associated Press

The Rev. Jesse L. Jackson, a protege of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and two-time presidential candidate who led the Civil Rights Movement for decades after the revered leader’s assassination, has died. He was 84. (AP)

The Rev. Jesse Jackson, who died Tuesday at the age of 84, was known not just as a tireless advocate for the Civil Rights Movement but as one of its most dynamic orators.

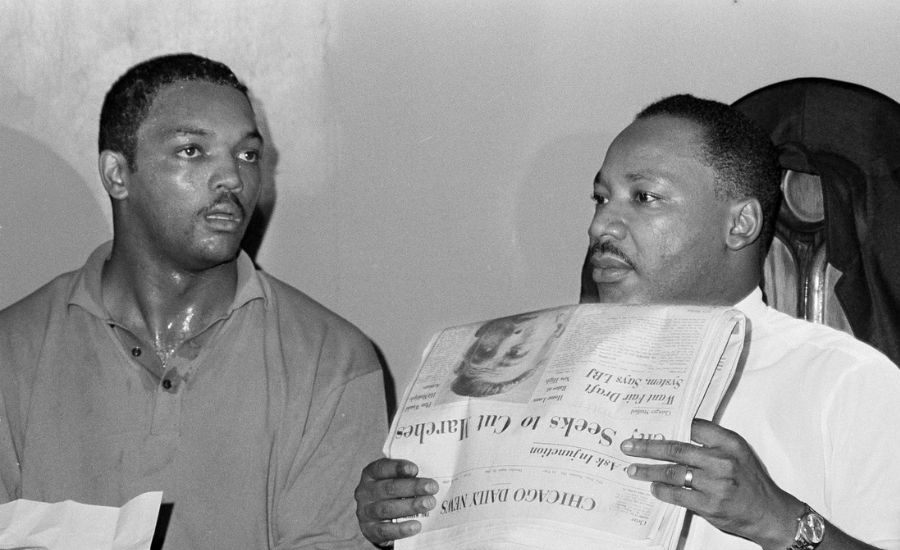

As a young organizer in Chicago, Jackson was called to meet with Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, shortly before King was killed, and he publicly positioned himself thereafter as King’s successor.

Santita Jackson confirmed that her father, who had a rare neurological disorder, died at home in Chicago, surrounded by family.

He spoke tirelessly for the poor and marginalized on issues from voting rights to housing. Jackson also gave numerous speeches as the leader of the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition and as a presidential candidate in the 1980s. In his later years, he did the same for the Black Lives Matter movement.

Civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., right, and his aide Rev. Jesse Jackson are seen in Chicago, Aug. 19, 1966. (AP Photo/Larry Stoddard, File)

When he declared, “I am Somebody,” in a poem he often repeated, he sought to reach people of all colors. “I may be poor, but I am Somebody; I may be young; but I am Somebody; I may be on welfare, but I am Somebody,” Jackson intoned.

It was a message he took literally and personally, having risen from obscurity in the segregated South to become America’s best-known civil rights activist since King.

“Our father was a servant leader — not only to our family, but to the oppressed, the voiceless, and the overlooked around the world,” the Jackson family said in a statement posted online. “We shared him with the world, and in return, the world became part of our extended family.”

Here are some notable and defining words from Jackson.

America as a patchwork quilt

At the Democratic National Convention in 1984 during his first run for president, he said:

“America is not like a blanket—one piece of unbroken cloth, the same color, the same texture, the same size. America is more like a quilt: many patches, many pieces, many colors, many sizes, all woven and held together by a common thread.”

‘Keep hope alive’

He offered encouragement in his convention speech four years later, when he nearly captured the 1988 Democratic nomination:

“You must not surrender. You may or may not get there, but just know that you’re qualified and you hold on and hold out. We must never surrender. America will get better and better. Keep hope alive. Keep hope alive. Keep hope alive. On tomorrow night and beyond, keep hope alive.”

Crime in the ‘90s

To students at Kansas State University in November 1993 about taking a stand against the rise in violent crime, he said:

“At this stage we are on the defensive as a struggle, as a humane struggle. Fear: it is pushing hope back. Cowardice is pushing courage back. Death is taking the joy of life. Dope is outdistancing hope. Escapism is outdistancing embrace. When youth come alive, you have the energy, the strength, the need, and the moral authority to make America better and the whole world more secure.”

‘More futures and fewer young funerals’

In Virginia, at the dedication of the Martin Luther King Jr. Bridge in September 2008, he said of the new span:

“It must lead to more futures and fewer young funerals. It must embrace Dr. King’s last dream, a poor people’s campaign, where all could come together with a job, income, education, and health care. A bridge that leads us from racial battleground to economic common ground. It leads us to healing.”

Former South African President Nelson Mandela, left, walks with the Rev. Jesse Jackson after their meeting in Johannesburg, South Africa, Oct. 26, 2005. (AP Photo/Themba Hadebe, File)

Dare to dream big

To students at the Cambridge Union Society in England in December 2013, he said:

“Common ground leads to coalition, to cooperation, to reconciliation and redemption, and to higher moral and economic ground. The challenge of this new world, so connected by technology, is yours to bear and yours to share. I want to say to you young people especially — keep reaching beyond your grasp, keep dreaming beyond your circumstances, keep dreaming of a new Europe. When young people move, the world changes.”

About the respected leader

Jesse Louis Jackson was born Oct. 8, 1941, in Greenville, South Carolina, the son of high school student Helen Burns and Noah Louis Robinson, a married man who lived next door. Jackson was later adopted by Charles Henry Jackson, who married his mother.

Jackson was a star quarterback on the football team at Sterling High School in Greenville, and he accepted a football scholarship from the University of Illinois. But after reportedly being told that Black people couldn’t play quarterback, he transferred to North Carolina A&T in Greensboro, where he became the first-string quarterback, an honor student in sociology and economics, and student body president.

Arriving on the historically Black campus in 1960 just months after students there launched sit-ins at a whites-only lunch counter, Jackson immersed himself in the blossoming Civil Rights Movement.

By 1965, he joined the voting rights march King led from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. King dispatched him to Chicago to launch Operation Breadbasket, a Southern Christian Leadership Conference effort to pressure companies to hire Black workers.

Jackson called his time with King “a phenomenal four years of work.”

Jackson was with King on April 4, 1968, when the civil rights leader was slain. Jackson’s account of the assassination was that King died in his arms.

In 1971, Jackson broke with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to form Operation PUSH, originally named People United to Save Humanity. The organization based on Chicago’s South Side declared a sweeping mission, from diversifying workforces to registering voters in communities of color nationwide. Using lawsuits and threats of boycotts, Jackson pressured top corporations to spend millions and publicly commit to hiring more diverse employees.

His wife, Jacqueline Lavinia Brown, the college sweetheart he married in 1963, helped raise their five children: Santita Jackson, Yusef DuBois Jackson, Jacqueline Lavinia Jackson Jr., and two future members of Congress, U.S. Rep. Jonathan Luther Jackson and Jesse L. Jackson Jr., who resigned in 2012.