Black History Month Reflection: Why Richard Smallwood’s Music Still Matters

By Alexis O’Hara // EEW Magazine Online

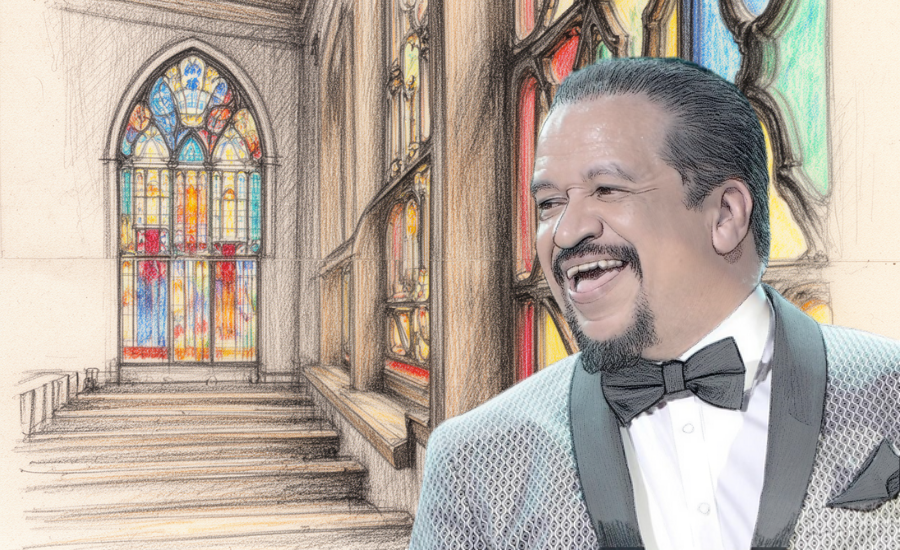

An illustrated tribute to Richard Smallwood, whose music remains foundational to Black worship and sacred excellence. (Credit: EEW Magazine)

Editor’s Note | Black History Month

As we begin Black History Month, EEW Magazine is committed to honoring not only public figures and political milestones, but the spiritual architects who shaped Black life from within the sanctuary.

Richard Smallwood’s legacy is a reminder that Black history includes the sounds that sustained us, the worship that formed us, and the sacred excellence that taught us how to honor God with our whole selves.

This reflection is offered not as a farewell, but as a recognition of a legacy that continues to sing.

As Black History Month begins, the passing of Richard Smallwood invites a different kind of reflection. Not one centered on the moment of his death, but on the permanence of his contribution.

For more than four decades, Smallwood shaped how Black churches worship, mourn, rejoice, and remember God. His music did not simply accompany Black faith. It instructed it. It disciplined it. It dignified it.

Smallwood, who died Dec. 30, was a classically trained composer, a scholar of sound, and a servant of the sanctuary. Born in Atlanta and raised in Washington, D.C., he studied music at Howard University and went on to found the Howard Gospel Choir in 1968.

An illustrated tribute to Richard Smallwood, whose music remains foundational to Black worship and sacred excellence. (Credit: EEW Magazine)

That decision alone reshaped the musical and spiritual life of one of the nation’s most storied historically Black universities, fusing academic rigor with sacred expression.

But his influence did not remain confined to lecture halls or choir lofts. It poured into churches across the country through compositions that became modern hymns. Songs like “Total Praise,” “Center of My Joy,” and “I Love the Lord” transcended performance and entered collective memory. They were sung in moments of national grief and personal heartbreak, during altar calls and at funerals, in sanctuaries and living rooms alike.

What distinguished Smallwood was not only what he wrote, but how he believed worship should be approached. Those who worked with him consistently described his insistence on preparation, precision, and reverence. For Smallwood, the choir loft was holy ground. Excellence was not ego. Discipline was not rigidity. Preparation itself was an act of praise.

That philosophy shaped generations of musicians and worship leaders, particularly in Black churches where gospel music has long served as both theology and testimony. Smallwood demonstrated that worship could be intellectually demanding and spiritually accessible at the same time. His compositions required attention, rehearsal, and humility. They could not be rushed. They could not be faked.

That mattered then. It matters now.

In recent years, as worship culture has trended toward informality and immediacy, Smallwood’s body of work stands as a reminder that sacred art carries weight. His music asked something of the worshipper. It called for breath control, harmonic unity, and emotional honesty. It reminded congregations that praise is not casual, even when it is joyful.

His songs also carried theology. “Total Praise,” rooted in Psalm 121, offered language for trust in seasons of exhaustion and uncertainty. “Center of My Joy” articulated contentment grounded not in circumstance, but in Christ. These were not vague affirmations. They were doctrinal statements set to melody.

At a memorial service held in January at First Baptist Church of Glenarden in Maryland, faith leaders, musicians, and public figures testified not only to Smallwood’s genius, but to his humility. They described a man who understood his gift as stewardship, not spotlight. A composer who believed that what was offered to God should reflect care, order, and reverence.

That legacy places Richard Smallwood squarely within Black history, not just gospel history. His work belongs alongside the spirituals, the hymns, and the freedom songs that have carried Black people through centuries of struggle and survival. His music served as soundtrack and shelter, helping communities articulate faith in moments when words alone were insufficient.

As Black History Month begins, Smallwood’s life reminds us that history is not only written in speeches and marches, but in songs sung together. In harmonies learned over time. In music that outlives its composer and continues to speak.

Richard Smallwood once said he wanted to write music that would be sung long after he was gone. By every measure that matters, he succeeded.